Violent backlash against US foreign policy

by Raymond Barrett

The killing of the US ambassador to Libya coupled with an eruption of anti-American protests in Middle East capitals indicates that Washington has unleashed forces it cannot control by supporting revolutionaries across the region.

Ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans men died after a consulate in Libya’s second city of Benghazi came under rocket and gun attack on Tuesday evening during a protest over a US-made film deemed insulting to the prophet Mohammed.

Ansar al Sharia, a militant group involved in the overthrow of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, has been linked to the attack.

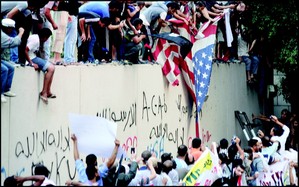

The events in Benghazi were followed by a wave of unrest that saw protestors killed in Yemen, Sudan, Tunisia, and Lebanon outside US embassies, schools and businesses as US Marines were deployed to the region to protect potential targets. In Cairo, demonstrators scaled the walls of the embassy and tore down a US flag before being driven back by security forces.

In Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula bordering Israel, a UN peacekeeping force under US command also was attacked by a group of over 50 men. The unrest even spread as far as Australia last Friday, when several hundred people who were protesting outside the US Consulate in Sydney, clashed with police. Officers used pepper spray to fend off protestors, who were reportedly throwing rocks and bottles, and there were eight arrests.

While the “anti-Islamic” film, reportedly produced by an Egyptian Christian living in California, was blamed for the violence, the scale of the protests hints that US foreign policy towards the entire Middle East region may need drastic revision.

Protesters destroy an American flag pulled down from the US embassy in Cairo last Tuesday. Photo: Getty

Libya after Gaddafi

When the Arab Spring finally reached Gaddafi’s Libya in February 2011, France, the UK and the US provided air-support to the rebels as they fought from their base in Benghazi to seize the capitol – Tripoli.

However, there was an elephant in the room that the Obama administration and its allies strenuously ignored: many foreign jihadis who went to Iraq to fight the “US occupiers” after the 2003 invasion came from Benghazi.

Thus, the fact that some of these militants eventually turned their ire towards the US has an air of inevitability.

Isobel Coleman, a Middle East specialist with the Council on Foreign Relations, described the killing of the ambassador as a “well-planned attack – weeks in the planning” and its coinciding with the 9/11 anniversary as no accident.

Furthermore, al-Qaeda’s leader Ayman al-Zawahiri had called for revenge after a senior Libyan member of the group, Abu Yahya al-Libi, was killed in a CIA drone strike in Pakistan in June.

According to Coleman, the different groups that ousted Gaddafi “have not coalesced into a national government.”

And now the US finds itself in the middle of a conflict between Islamists and a nascent secular government each of whom have differing views on what a 21st century Islamic nation should look like.

Groups such as Ansar al Sharia, who take a literal reading of the Koran and are referred to as “Salafis”, have been linked to the destruction of a Sufi Muslim shrines they deemed idolatrous and an attack on the British ambassador in June.

“We have to deal with these militias because some of them have nothing to do with the revolution,” Libyan Prime Minister Mustafa Abu Shagour said this week.

But this puts Islamists on a collision course with both the Libyan government and its American allies.

“There’s always the potential for violence – It’ll get worse before it gets better,” Coleman said, who described these events as “a wake-up call to the [Libyan] government.”

Regional implications

Despite the severity of the incident in Benghazi, Libya is only a microcosm of a much larger problem. With Libya relatively isolated from the more cancerous geo-politics of the Middle East, a surge in anti-American sentiment in Egypt, Yemen and Syria would have far greater ramifications, especially for their immediate neighbours – Israel, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Lebanon – and US strategic objectives.

Whereas similar protests occurred over incidents such as Danish newspapers showing cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed in 2005, the regional strongmen supported by the US in the past like Hosni Mubarak are no longer in place to keep restive populations in check.

But it is in Syria where the US has chosen some of its strangest bedfellows. To oust president Bashar al-Assad, the Obama administration has authorized CIA support to Syrian rebel factions (comprised mainly of Sunnis) despite the local Christian and Shia population fearing such groups seizing power.

As the Syrian conflict has progressed, the jihadi element to the opposition (including Libyans) has intensified and Middle East specialists have identified sectarian killings and slogans such as “Christians to Beirut, Alawites to the tomb” as a worrying portent.

Despite the short-term gains of supporting militants to topple dictators, the long-term efficacy of this strategy for the US is still unclear. Despite receiving support from the US, the Free Syrian Army will look unfavorably on Washington’s support of Israel given the latter’s occupation of the Golan Heights.

US domestic reaction

Yet such considerations largely have been absent from the political discourse in the US. But the killings in Benghazi have given foreign policy concerns a greater public profile in a presidential campaign focused on the domestic economy.

As the protests spread, some Republican Congressmen called for aid to Egypt and Libya to be cut, especially after Egypt’s president Mohammed Mursi appeared lukewarm in his condemnation of attacks on the US embassy.

In response, Obama described Egypt’s new Muslim Brotherhood government in unusually tepid terms, describing the country it gives $1.3 billion in military aid annually as neither an ally nor an enemy.

The current unrest also was an opportunity for Republican nominee Mitt Romney to score some foreign policy points against Obama, who has been bolstered on this front by the killing of Osama Bin Laden in May 2011.

Romney criticized the president for kowtowing to the Muslim world, while the Obama hit back by accusing his opponent of “a tendency to shoot first and aim later.”

Yet few US politicians will admit that the Islamist groups Obama is now befriending bear an uneasy likeliness to the militants president Ronald Reagan supported in Afghanistan in the 1980s, who would eventually return to haunt the US to such a devastating effect.

Raymond Barrett is the author of Dubai Dreams: Inside the Kingdom of Bling

© Post Publications Limited, 97 South Mall, Cork. Registered in Ireland: 148865.

Post a Comment